UkraineWorld spoke to Serhy Yekelchyk, Professor of History and Slavic Studies at the University of Victoria, President of the Canadian Association of Ukrainian Studies.

Key points — in our brief, #UkraineWorldAnalysis:

1. On the novelty of Intellectual History

- Intellectual History differs from the old-fashioned History of Ideas in that it puts theoretical notions in their proper social and cultural context. It shows how ideas emerge or arrive from another culture and why they become important.

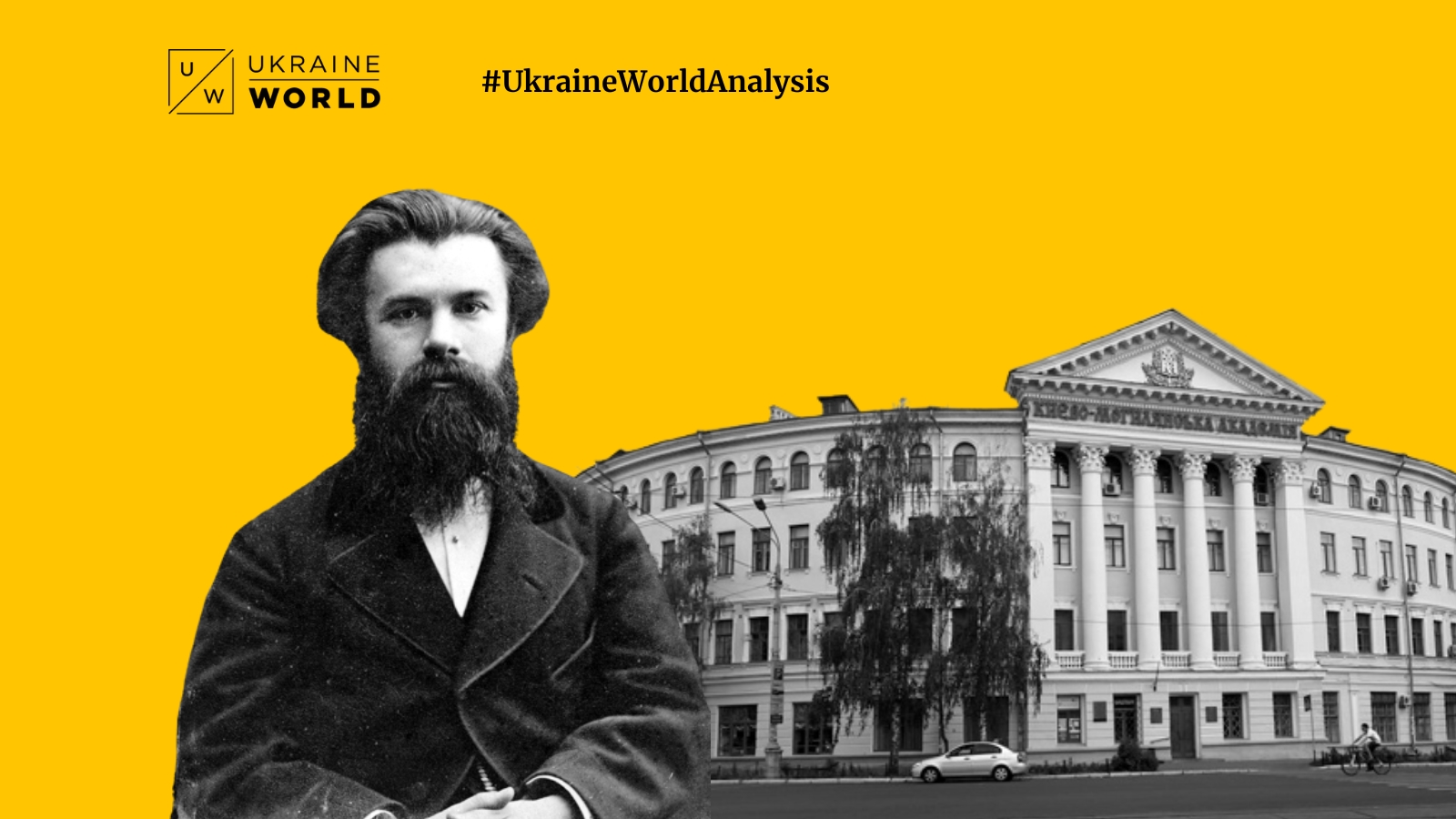

- Intellectual History is particularly important in the Ukrainian case because under Russian and Austrian imperial rule philosophy was considered a sublime discipline only accessible in imperial languages and best practiced in imperial capitals. The Russian Empire quickly forgot that in the eighteenth century their own philosophical knowledge came from Ukraine — from Kyiv Mohyla Academy and European-educated Ukrainian clergymen.

- The intellectual history of Ukraine is a relatively new discipline, but it is building on the work that several prominent Ukrainian historians of philosophy did during the late Soviet period. Valeriia Nichyk and Vilen Horsky wrote important studies of what was then called "philosophical ideas" in Ukrainian culture. Horsky's book on Kyivan Rus′ and Nichyk's work on Western European humanistic influences in Ukrainian culture, Kyiv Mohyla Academy, and Feofan Prokopovych were outstanding examples of Ukrainian intellectual history before such a term was in use in Ukraine. Similarly, some Ukrainian historians managed to publish important works on what was then called the history of sociopolitical ideas or "cultural life."

2. On the ideological battlefield

- Developments in the field were closely monitored by Soviet ideologists. My dissertation supervisor, Vitalii Sarbei, had his Doctor of Sciences dissertation rejected because it dealt with the legacy of the prominent Ukrainian thinker Mykhailo Drahomanov. He had to write another one — about Marx and Engels and Ukraine — an interesting topic if addressed critically, but this was not something the ideologists would allow.

Drahomanov himself was probably the first modern practitioner of Ukrainian intellectual history.

- His diverse research interests ranged from historical songs and symbols of the nation to "Shevchenko, peasant-lovers, and socialism" (the latter title of his important book). He was also the first modern thinker to insist on the European character of Ukrainian culture and political thought before imperial suppression.

- If the rediscovery of Drahomanov in the late 1980s fit well with the ideas of the Rukh movement and contemporary hopes for a civilized divorce from Russia, the subsequent lionization of two other major figures marked the transition to Ukrainian independence and state building. The great historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky was always interested in the Ukrainian national movement during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. After his return to Soviet Ukraine in 1924, Hrushevsky introduced these topics into the research program of the academic institutions he headed. Such research effectively overcame the impediment of there not having been a Ukrainian state during that period — the Ukrainian intellectual tradition was alive even in the darkest times of tsarist oppression. The sociologist Viacheslav Lypynsky approached the Ukrainian cultural and intellectual tradition differently, through an emphasis on the native social elites that were never completely lost to assimilation. His dense, theoretically informed writings influenced historians in independent Ukraine more as an example of a methodology diametrically opposed to the Soviet one, and in so doing shaped the statist trend in Ukrainian intellectual history of the 1990s and early 2000s.

3. On modern Ukraine's Intellectual History

- The Ukrainian revolutions of 2004 and 2014 demonstrated the significance of a wider approach that is characteristic of intellectual history. Philosophers did not have to define Ukraine's "European" choice; there was already a widespread understanding of what it stood for: political freedom, rule of law, power of the people. In fact, some Western intellectual historians (Marci Shore) spoke of the return of metaphysics as a result of the Maidans.

The ontological understanding of good and evil became possible because of the two Ukrainian revolutions.

- The commemoration of the Heavenly Hundred demonstrated the same shared understanding of human rights and individual choices undoing the Soviet legacy of collectivism and the leader principle. Those hundred people who were killed on Kyiv's Maidan are represented as a community of individual portraits and names. Individual choices are important, so we remember the Revolution of Dignity by the faces of its defenders.

- Ukraine is rewriting world history by fighting for global democracy against Putin's authoritarian Russia. In the nineteenth century, Mykola Kostomarov wrote about the Ukrainian historical tradition of democracy, tracing it to the ancient viche (citizen assembly). He used this supposition to construct a modern Ukrainian ethnic nation. For us in the twenty-first century, it is the opposite: the modern democratic society develops from the Ukrainian national movement, but creates a political, civic Ukrainian identity. Putin seems to be thinking in terms of a bygone intellectual tradition, that of Hitler and Mussolini, in which ethnic membership determined political loyalty. But in Ukraine he is facing an opponent fully in tune with the trends of the twenty-first century. The country in which the people can rally around Mustafa Nayem, Serhii Nihoian, or Volodymyr Zelensky, represents a challenge that the Russian political elites simply cannot comprehend.

- We need intellectual history in order to understand why Ukraine can build such a nation while Russians cannot even make sense of what today's Ukraine is. Even so-called "good Russians" seem so distant and estranged from things that are crystal-clear to every Ukrainian, young and old.

DARIA SYNHAIEVSKA, ANALYST AND JOURNALIST AT UKRAINEWORLD

Serhy Yekelchyk, Professor of History and Slavic Studies at the University of Victoria

This material was prepared with financial support from the International Renaissance Foundation.