In the late 1920s to early 1930s, Soviet authorities continuously targeted different groups of intellectuals with repressive measures. Among them, trials against the so-called "Union for Ukraine's Liberation" (SVU) – an organization practically invented by USSR's special police – were some of the most massive.

During that episode, 45 people were accused in 1930 of organizing an armed uprising to overthrow the Soviet regime in Ukraine, of terror against communist leaders, and of foreign interference. The rebels were led by Serhiy Yefremov, a Ukrainian academic and the Deputy Director of Ukraine's National Academy of Sciences, according to the official investigation. Other participants in the alleged conspiracy included former politicians and governors of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic, as well as scientists, university professors, students, schoolteachers, priests, writers, editors, lawyers, a librarian and a school principal. Most of these defendants were imprisoned for one to ten years, and though some were pardoned or given conditional detentions, all of these prosecutions had a second function: to set a precedent for future repressions.

Soon, another 700 people were accused in connection with the SVU – a number that may have reached as high as 30,000, according to some researchers. And the frequently, their prosecution lapsed into the absurd: for instance, the SVU was alleged to have maintained a medical faction tasked with hurting communist patients. Such details demonstrate how threatened Soviet authorities felt by Ukrainian intellectuals: ultimately, their attempts to imprison individuals who they found dangerous or harmful expanded into elaborate theories of conspiracy – and equally draconian attempts to break them up.

Such repressions would have catastrophic consequences for an entire generation of Ukrainian writers and artists. Relatively liberal tendencies during the 1920s – the development of education and the comparative leniency of the Soviet regime – helped to foster a wide range of art movements and schools. But this flourishing, later named the Executed Renaissance, came to a tragic end: the era’s prominent figures were often imprisoned and even executed on charges of terrorist activity. The poet-futurist Mykhailo Yalovy and writer-satirist Ostap Vyshnya, for instance, were accused in 1933 of spying and attempting to assassinate the Soviet official Pavel Postyshev. In 1937, poet Mykhayl Semenko was executed as an alleged member of a terrorist organization, and charged with attempting to assassinate Stanislav Kosior, Ukraine’s communist party leader.

Those accusations were completely fabricated, but by building such cases, the Soviet regime worked to build an image of Ukrainian intellectuals as aggressive nationalists and terrorists.

Though the Soviet Union was officially declared an atheist state, the government’s attitude towards religion varied over time and from church-to-church. Due to its connection with the West through the Roman Pope, along with its tradition of support for Ukrainian national movement, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church was among the most repressed.

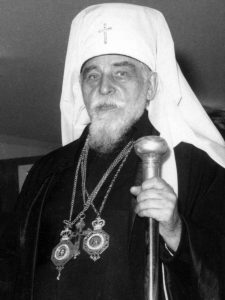

In 1944, that church elected Josyf Slipyj as its Major Archbishop. When Soviet troops entered Western Ukraine half a year later, however, Slipyj was arrested and accused in collaboration with Nazis. Soon after that, the Soviet regime announced the liquidation of the Greek Catholic Church and its “reunification” with the Orthodox Church. Authorities demanded that Slipyj join the Orthodox Church as a condition of his release, but he refused to deny his denomination; ultimately, he spent 18 years imprisoned in Soviet camps. Slipyj was finally released in 1962 due to personal efforts of the Pope John XXIII, and spent rest of his life in Rome.

Levko Lukyanenko, a prominent defender of human rights in Ukraine, was imprisoned for 27 years. He had worked in the military, as a civil servant, and as a lawyer before attempting to establish an underground party, “The Ukrainian Workers’ and Peasants’ Union” in 1960; he and his allies were arrested immediately after producing a draft version of the party programme. Its call for Ukrainian secession from the USSR became grounds for Lukyanenko’s death sentence by the Soviet court, even though that right was enshrined in the Soviet Constitution of 1936; 72 days later, the Supreme Court changed the verdict to 15 years of imprisonment.

Upon his release in 1976, Lukyanenko headed the Ukrainian Helsinki Group – a human rights organisation that monitored the Soviet government’s compliance with the Helsinki Accords. This soon led to his second imprisonment. After his final release in 1988, Lukyanenko actively participated in Ukrainian national-democratic opposition movement, wrote the text of the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine (1991) and was repeatedly elected as a member of Ukraine’s parliament. He died at 89 years old in July of this year.

Vasyl Stus was a prominent Ukrainian poet of the twentieth century and a key figure of Ukrainian dissident movement. In 1965, Stus, along with a group of other activists, made a uniquely brave statement: during a showing of “Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors,” a movie by Sergey Paradzhanov, they protested against the arrests of Ukrainian intellectuals. This has been regarded by some historians as the first public protest against political repressions in the Soviet Union after World War II, and marked the beginning of the “Sixtiers” dissident movement in Ukraine.

Stus was expelled from his university’s post-graduate programme for his efforts, but this did not stop him from protesting. Ongoing criticism of the Soviet regime for human rights violations and the arrests of his colleagues led to Stus’ arrest in 1972; he was accused of anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda (a common charge levelled against dissidents) and sentenced to 8 years of exile and imprisonment. During that time, Stus wrote a letter to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union rejecting his Soviet citizenship: “To be a Soviet citizens means being a slave,” he wrote.

Only a year after his prison sentence, Stus was once again arrested – this time on “possession of hostile literature” in order to “undermine and weaken Soviet power”. On these charges, he was sentenced to 15 more years of prison and exile. Five years later, he died under mysterious circumstances, possibly with the involvement of the camp’s personnel, who denied him medical assistance and detained him under dangerous conditions. Most of the lyrics he wrote in prison were destroyed.

Mustafa Dzhemilev, a Soviet dissident and leader of the Crimean Tatars’ national movement, continues his fight for the rights of Crimean Tatars after Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea. He was has been sentenced to prison seven times for a total of 15 years, all for his beliefs and efforts to protect the rights of his people.

As a child in 1944, Dzhemilev’s family was deported from his village of Crime to Uzbekistan as part of a mass deportation of Crimean Tatars. He was involved in the national movement of Crimean Tatars from the age of 16; after entering university, he was expelled for distributing a historical manuscript he wrote about Turkic culture in Crimea. Then, he was imprisoned for refusing to serve in the Soviet Army on political grounds; there, he held repeated hunger strikes in protest of violations of prisoner rights. The famous Soviet human rights activist Andrei Sakharov called for his release on several occasions.

Dzhemilev, after his release from prison in 1987, made a significant contribution to the repatriation of Crimean Tatars to their homeland: he headed Mejlis, the highest executive-representative body of the Crimean Tatars, from 1991 to 2013. Today, as a Ukrainian MP, he actively protests against the occupation of Crimea by Russia and fights for the release of Moscow’s new political prisoners.

Throughout history, intellectuals have suffered from Soviet law enforcement; in Russia, some things never change. The Sentsov case has been fabricated following a playbook that dates back to Soviet times, accused of organizing terrorism; the Kremlin, meanwhile, continues to portray Ukrainians as terrorist and traitors, especially Ukrainian intellectuals and leaders.