Even this is not the last step on the way towards land restoration, ecologists warn. The Eastern Variant has learned how much demining the agricultural lands of Donetsk Oblast could cost, how shells can poison the ground, and why the steppe near Mariupol must be restored.

Viktor Batytskyi, a 65-year-old farmer, has been working on these lands for over 30 years. His wheat and sunflower fields are 140 km from the contact line. But even there, in the relatively peaceful Pokrovsk District of Donetsk Oblast, the echoes of war can be heard. It has already been a year since Viktor Batytskyi sheltered his old friend, a 75-year-old Oleksandr Kvitnytskyi, a farmer from near the town of Lyman. Located only 13 km from the front line, his village of Kolodyaz is still under heavy shelling.

"On April 17, 2022, my village fell under occupation. The day before, I had managed to take my family to Viktor Batytskyi's farm, and we've been living here for a year," Oleksandr Kvitnytskyi recounts.

He left behind 800 hectares of land and lots of equipment in his village. But these were not Kvitnytskyi's biggest losses.

"My wife was left behind at home forever. She was killed by shrapnel."

He has managed to partially evacuate his equipment to Batytskyi's farm in the western part of Donetsk Oblast.

"We managed to take out three tractors and a combine harvester, but a lot of equipment remained behind. I had just taken out a UAH 2 million loan for some new equipment. Only in March of this year did I manage to repay the debt," Oleksandr explains.

The farmer believed until the last moment that his village would survive, and continued to work in his fields under fire.

Oleksandr Kvitnytskyiy says, "The boys promised that they would never let them break through. I bought all the fertilizers and diesel fuel for the spring season. I fertilized the winter wheat that had been growing on 250 hectares. There also remained 60 hectares of unharvested corn, 100 tons of wheat grain in the elevators, and the same amount of sunflower and soybeans."

Now, all Kvitnytskyi's warehouses and equipment have been ruined, and the grain has disappeared from the warehouses.

"The grain was taken away by the Russians during the occupation, and my planters were looted by locals who stayed behind," Oleksandr Kvitnytskyiy continues.

Now, about 30 out of 300 pre-February 2022 residents remain in the village of Kolodyazy, the farmer says. From the very first day of the occupation, the Russians started shooting the villagers.

Photo by Oleksandr Kvitnytsky’s ruined farm.

Photo by Oleksandr Kvitnytsky’s ruined farm.

Oleksandr Kvitnytskyi recalls how , “first they killed a man, then a woman, then they shot a farmer. The same fate awaited me as well.”

After the Ukraine liberated Lyman and the neighboring villages in October 2022, some local farmers returned home with the hope of going back to their fields. However, the region is still under heavy shelling. Oleksandr Kvitnytskyi visited his village twice, only to realize that it was too early to return there for good.

"Driving from Lyman to the village, on both sides of the road you can see shell-cratered fields, unharvested wheat and abandoned livestock. Some farmers brought their equipment back straight after the liberation, but the Russians began to attack the area from Kreminna. Thus, the farmers had to take their equipment out again," Kvitnytskyi explains.

Now, the farmers of the liberated Lyman District are anxiously awaiting victory, but they see the future as uncertain.

As Oleksandr explains, "Everyone wants to come back home, but the fields have been mined. Some farmers from the areas of Lyman that are not being shelled have resumed their work at their own peril and risk. They inspect their fields themselves, find mines, and mark them. After that, they get in their harvesters and drive around the mines."

Even farmers who are far from the front line have been experiencing the impact of the war. Viktor Batytskyi states that the war has exacerbated issues with logistics and bringing products to market, leading to a drop in the price of grain.

"Previously, we sold everything through Mariupol and Berdyansk, but now we have to deliver everything to Odessa. And the farther the grain is from the port, the cheaper it is. Before the war, wheat used to cost UAH 8,000 per ton, and now it is down to UAH 5,000 per ton. Sunflower seeds used to cost UAH 22,000 per ton, and now they cost UAH 14,000 per ton," Batytskyi explains.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Artem Chahan, the director of the Department of Agricultural and Industrial Development and Land Relations for the Donetsk Oblast Military Administration, concurs.

"The cost of grain production has increased significantly. Previously, transportation of a ton of wheat to Mariupol or Berdyansk cost UAH 300, but now transportation to Odesa costs UAH 3-4,000. This means a cost increase of almost USD 100 per ton. This is another reason for the drop in the prices farmers are receiving for their crops and for the changes in the structure of the cultivated areas. The farmers break even, or even go into the red."

The Donetsk Oblast Military Administration reports that 643.7 thousand hectares of the region are currently under temporary occupation. Only 36% of the area which was controlled by Ukrainian authorities at the beginning of the full-scale war remains so.

Overall, since the armed conflict started in 2014, Ukraine has lost 57% of the oblast's total territory to Russian aggression and occupation. The acreage of cultivated land in the oblast has thus decreased by 57%. Animal husbandry has been affected, as well, with the number of cattle being raised falling by 48%.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Farmers have managed to take some animals to safer regions of Ukraine, but many animals have died. According to department statistics, 1,034 cattle, 20,900 pigs, and 1,023,000 poultry birds have died. The cost of livestock death in Donetsk Oblast has been estimated at UAH 209 million, and the destruction of livestock facilities is estimated at UAH 606.4 million.

The overall losses in the agrarian and industrial sector of Donetsk Oblast have been estimated at UAH 2.87 billion, with more losses to be added.

It will be difficult to restore the industry without help from Ukraine's international partners, Chahan adds.

"After our territory is liberated, we will launch a regional program to restore the disturbed lands. This will include demining. We hope to get at least three demining machines, which are very expensive, and we are counting on the support of our Western partners," he explains.

According to calculations by the Kyiv School of Economics, inspecting and clearing mine-contaminated territory in Ukraine will cost an estimated USD 436 million.

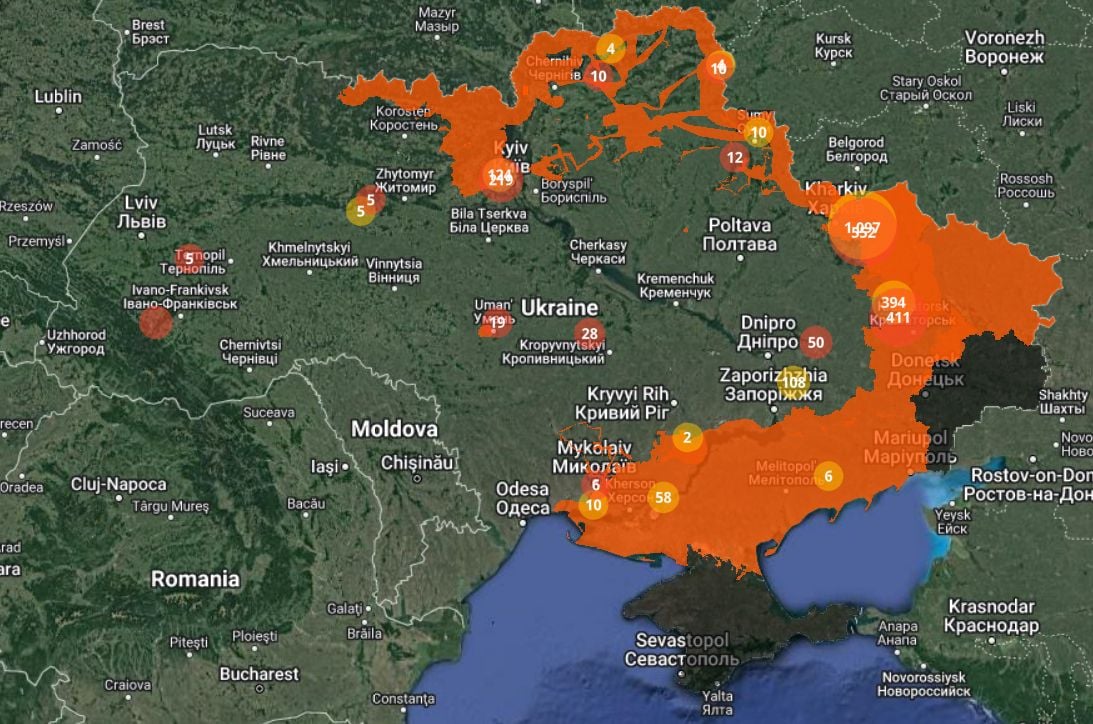

An interactive map of mined areas. Source: mine.dsns.gov.ua.

An interactive map of mined areas. Source: mine.dsns.gov.ua.

The Ukrainian Association of Sappers claim that farmers will simply not be able to provide for the demining of their lands at their own expense. Demining of a square meter of land costs USD 3-4.

One hectare is 10 thousand square meters, so even a farmer with a small 2-hectare land plot will have to spend from USD 60-80 thousand. Large farms on tens of thousands of hectares, and thus hundreds of millions of square meters, will cost a fortune.

The soil of Donetsk and Luhansk Oblasts has its own peculiarities. Even before the war, the region had high levels of both pollution and soil degradation. The war has added new problems, with a serious increase in the level of heavy metals in the soil of the two oblasts coming as a result of fighting since 2014.

According to a study by the NGO Ecoaction, soil samples taken between 2016 and 2020 from the Antiterrorist Operation / Joint Forces Operation zone (where the fighting of the Donbas War took place) showed high levels of lead, copper, arsenic, zinc, chromium, cadmium, molybdenum, barium, potassium, magnesium, and tungsten.

Photo by Eastern Variant. [Stop! Mines!]

Photo by Eastern Variant. [Stop! Mines!]

Anastasiya Splodytel, a candidate of geographic sciences and expert at Ecoaction, explains, "compared to readings from before the beginning of military actions in 2014, the heavy metal levels in the soil have increased by 3 to 25 times. In some individual samples, the background values have increased by a hundred times. In the areas shelled by artillery and rockets, the levels of cadmium, lead, zinc and mercury concentrations are the highest."

The consequences of chemical contamination of soil on human health can be seen in other countries affected by war.

Splodytel explains that these pollutants can contribute to a number of diseases and serious health problems.

"In the Gaza Strip, there has been an increase in the number of premature births and the prevalence of birth defects in newborns resulting from exposure to high levels of barium, arsenic, cobalt, and other chemicals. Some studies have also recorded disorders of neurological development in children from war zones in Iraq."

Between 2016 and 2020, researchers found an increased prevalence of stunted growth and neurological development delays in children associated with intrauterine exposure to such heavy metals as arsenic, barium, and molybdenum, which are among the heavy metals that have been recorded at high levels in the soil of lands in the Donbas warzone.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

In addition to chemical contamination, the soil in Donbas has been subject to the direct physical ravages of war. Vibrations from explosions compact the soil and form cavities, and emissions of heated air affect soil organisms. Demining destroys soil's humus horizon, which in turn affects the fertility of the land and its ability to retain water.

"Landmine clearance operations are often complex and expensive, and in developing countries, they usually mean a total depletion of the soil," Splodytel concludes.

According to the Ministry of Agrarian Policy, it is impossible to know for sure how long the demining of Ukrainian territory will take. One-third of rural lands have become potentially dangerous and require inspection. Usually, 1 day of combat actions results in a demining process that requires 30 days, but the process can drag on for years.

The most pessimistic estimate from the Ministry of Economy is that it would take about 70 years to demine all of Ukraine's mine-contaminated lands. The State Emergency Service has a more optimistic but nevertheless daunting forecast of up to 10 years.

At the same time, Oleksiy Burkovskyi, a conservationist from Donetsk Oblast, predicts that most farmers will never return to their farms because their lands will be impossible to either demine or clear.

"The state should buy this land out and preserve it in order to restore our natural ecosystem," he explains.

In previous instances of land restoration in other countries, governments have opted to put lands in permanent conservation. Oleksiy Vasylyuk, the head of the Ukrainian Nature Protection Group ( UNCG), explains that in parts of France that served as the front line in the First World War, 100 square kilometers remain demarcated as uninhabitable, with both residential and farming activities prohibited. The depopulated territory is called the Zone Rouge. The high cost of demining and the low value of the land made the government abandon their hopes to reclaim the land.

Instead, the land has been put in conservation forever, and a forest has been planted on it.

The Zone Rouge. Source: wikipedia.org.

The Zone Rouge. Source: wikipedia.org.

This is the fate that may befall some of Ukraine's lands after the war ends.

In 2022, Ecoaction experts analyzed the consequences of fighting in the Sartan community of Mariupol District of Donetsk Oblast. Scientists recommended conserving this agricultural land and further restoring it to a state of natural steppe.

Source: ecoaction.org.ua. Data Ecoaction’s study, The Impact of the Russia’s War against Ukraine on the Condition of Ukrainian Soils, 2022

Source: ecoaction.org.ua. Data Ecoaction’s study, The Impact of the Russia’s War against Ukraine on the Condition of Ukrainian Soils, 2022

[Level of Damage – Land Suitability Categories]

CATASTROPHIC – UNSUITABLE HIGH – CONDITIONALLY SUITABLE AVERAGE – POORLY SUITABLE LOW – SUITABLE VERY LOW – DEFINITELY SUITABLE

The analysis was carried out using satellite images and selected soil samples specially collected by the military for scientists. The images have made it possible to estimate the density of craters, while the soil samples provided information on heavy metal contamination.

Anastasiya Splodytel explains that "The heavy metal content is ten times higher than normal levels. The Sartan community was host to all sorts of military activity. We have a clear image of the use of thermobaric ammunition [highly-destructive incendiary bombs -- ed.]. Its high thermal conductivity [up to 1,000° C -- ed.] turned the soil into stone, devoid of moisture. We have also observed soil compaction caused by the movement of heavy military equipment, which makes the soil difficult to cultivate, impairing its fertility."

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Splodytel warns that agricultural production from these lands will produce contaminated products, which can cause a number of diseases. Natural characteristics of local soils will also contribute to this. "In Donbas, the black soil binds to pollutants (heavy metals, explosives, etc.) extremely strongly, so that they can easily penetrate into vegetation," she explains.

Lands that have suffered catastrophic damage have been recommended to be left for conservation. However, there is currently no legal mechanism in Ukraine to mandate agricultural land conservation, Oleksiy Burkovskyi notes.

He explains thatgovernment buy-outs for hopelessly mined or poisoned areas could be an effective remedy. The issue lies in the fact that Ukraine has the highest proportion of its territory dedicated to growing crops in Europe at 57%, compared to an EU average of 25%.

Oleksiy Burkovskyi explains that "even without ecologists, the state has already adopted rules obliging it to reduce the area of arable land to 41% and to increase the proportion of nature reserves to 15%. That means that Ukraine had already planned to withdraw some land from circulation before the full-scale invasion. Unfortunately, after 2022, we will have a lot of degraded land, which was fertile 1.5 years ago, and which no one will conserve. Buy-outs are a possible solution. This way, the state could both protect the rights of landowners and meet its goals for nature conservation."

The feather grass steppe. Source: wikipedia.org.

The feather grass steppe. Source: wikipedia.org.

However, conservation is only one of many methods of land reclamation. There is a technology available to counteract each type of pollution. Phytoextraction, for example, uses plants to draw heavy metals out of the soil which can then be disposed of. Cadmium is effectively absorbed by sunflowers, and o bidens, as well as willow and poplar trees.

Phytoevaporation uses plants to disperse certain heavy metals into the air. According to Ecoaction’s research, the cost of this method ranges from USD 150-250,000 per hectare.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

Photo by Eastern Variant.

For the moment, Ukraine has no clear strategy for the future of its mined lands, but the government has already established a priority plan for demining. The Ministry of Agrarian Policy plans to first survey farms growing vegetables and melons, then arable land, and then non-agricultural land.

Oleksiy Vasylyuk from UNCG warns that "some fields will never get into the queue. First of all, we will need to rebuild cities, but some of them will probably no longer have life again. Lyman, Popasna, Maryinka, and Vuhledar have been completely destroyed and are too dangerous for human habitation."

Although the process of land restoration will be long and difficult, there are some solutions to improve the situation. Today, ecologists see several important steps to be taken on the way to land restoration.

Ecoaction offers the following solutions:

The material was prepared as part of the competition “Environmental Chronicles of War: Record, Research, Tell Stories” implemented by the NGO “Internews-Ukraine” with the financial support of Journalismfund.eu.