The debate over security guarantees for Ukraine has shifted from a single “Article 5 or nothing” frame to complementary instruments such as a Coalition of the Willing assurance package, bilateral treaties, and EU-led industrial integration.

The political logic driving this plurality is simple: NATO accession remains the strategic end state,

but it is politically infeasible right now; therefore allies are designing side agreements that can give deterrence, resilience, and enforceability without immediate treaty enlargement.

As of 2025, key Western allies are crafting a layered architecture of assurances - short-term, long-term, and structural - that combines bilateral treaties, multinational commitments, industrial integration, automatic response triggers, and legally binding obligations.

One of the illustrations is the fact that 26 nations have now committed to providing post-war security guarantees to Ukraine, including a "reassurance force" by land, sea, and air. At the same time, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has insisted that genuine guarantees must precede any peace settlement, warning that without them Russia could rebuild its strength and strike again.

What are the core building blocks of the guarantees under discussion? First, there are bilateral treaties in which individual states commit to Ukraine’s defense with specific obligations - weapons transfers, training, access to bases, logistics, and predetermined response mechanisms if Russia re-attacks. As former Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba explained, these will be framework agreements signed with each state that joins the guarantee bloc.

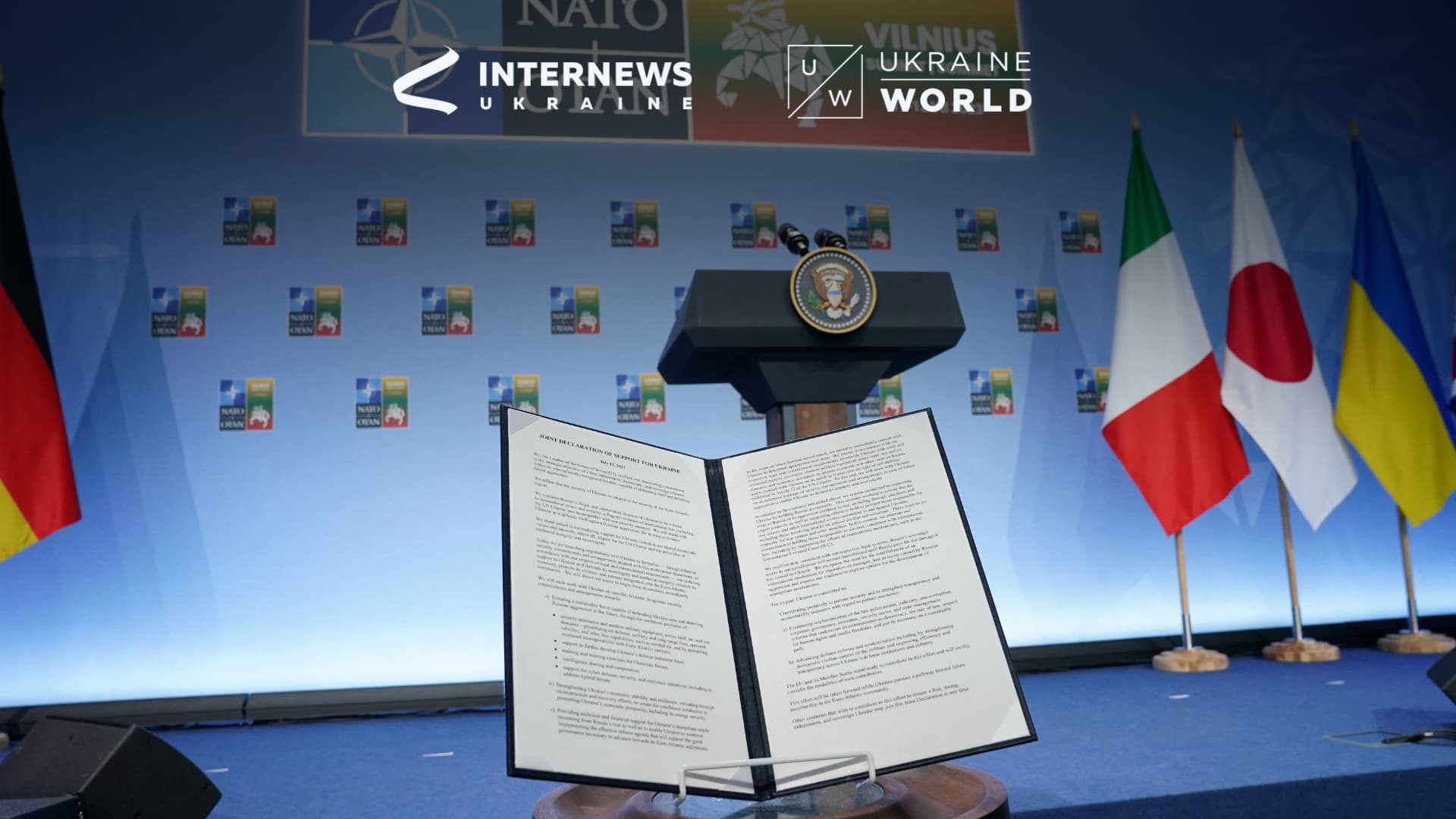

Stemming from the G7 Joint Declaration of Support for Ukraine signed in Vilnius in July 2023, this framework is a multilateral commitment to a system of bilateral, long-term security agreements with Ukraine. The focus is on ensuring Ukraine possesses a powerful, modern, and interoperable military capable of deterring future attacks on its own, an approach called "deterrence by denial."

A key premise holds that Putin would avoid launching another assault on Ukraine if Russia either lacks the means or sees little chance of success. While the first factor cannot be guaranteed over time, the second can be influenced. If Ukraine maintains or gains access to strong defensive capacities capable of repelling any future offensive, the probability of renewed Russian aggression would diminish substantially.

This is a significant shift from "deterrence by punishment"

(like NATO's Article 5), which promises a collective response after an attack. The agreements are explicitly designed as a bridge or a temporary assurance until Ukraine achieves its strategic goal of NATO membership, which is viewed by Kyiv as the only ultimate and genuine security guarantee.

Under this format rather than a single treaty, a network of individual, long-term bilateral agreements is being signed. Countries like the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and others are committing to:

In June 2024 Ukraine signed a 10‑year pact with the United States, committing the U.S. to work with allies to deter aggression. Germany signed a comprehensive security cooperation agreement in February 2024 stating it will “provide unwavering support for Ukraine for as long as it takes” and help it “defend itself [and] restore its territorial integrity”.

Ukraine and Poland signed a security co-operation treaty in July 2024, as did the UK (formally a “100-year partnership” signed in January 2025). In these deals, partners pledge long-term military aid, training, and defense-industrial support under agreed goals. For instance, the UK-Ukraine partnership explicitly covers maritime security, energy, and critical minerals cooperation.

None of the agreements creates binding collective-defense obligations like NATO’s Article 5 – they do not require guarantors to send troops in Ukraine’s defense. All triggers are limited to major attacks: each pact stipulates consultations and aid if Ukraine is “attacked again,” typically defined as an armed attack under the UN Charter.

A separate concept is the so-called “Coalition of the Willing”

(sometimes called a “reassurance force”). In September 2025 France and the UK convened 35 allied delegations in Paris (President Macron and PM Starmer co-chaired) to finalize postwar guarantees for Ukraine. Twenty-six countries publicly agreed to commit forces “on land, at sea and in the air” after a ceasefire or peace agreement.

This pledge was never fully defined but seems to envisage a multinational force or rotating deployments on Ukrainian territory and shared air/maritime patrols. Macron and Starmer said some partners (notably France and Britain) would “deploy to Ukraine” when safe, while others (e.g. Italy) would support from outside through training and equipment. President Zelenskiy welcomed the coalition as “the first time something very specific, serious” has been agreed.

In addition to military pacts, Ukraine and its partners have proposed economic and industrial guarantees to underpin security. The idea is to anchor Ukraine’s economy so deeply into the West that aggression becomes prohibitively costly. One thread is supply-chain integration: this includes tying Ukraine into Western industries and infrastructure.

For example, a 2025 US-Ukraine Critical Minerals Framework commits both sides to develop Ukraine’s mines for integration into Western green-energy supply chains. The UK-Ukraine 100-Year Partnership identifies cooperation on energy, critical minerals, and green steel, embedding Ukraine in long-term industrial projects.

EU programs (e.g. the Ukraine First initiative) and liberalized trade (deepened by EU accession talks) similarly aim to make Ukraine a key market and producer for Europe. These measures are strategically valuable by creating mutual dependency, but they take years to materialize and assume continued peace.

Another aspect is using frozen Russian assets. Western governments have amassed hundreds of billions of dollars in Russian central-bank reserves since 2022. Officials now propose channeling those funds to Ukraine. In late 2025 EU leaders neared agreement on an EU Commission plan to lend €140 billion (interest-free) to Ukraine secured by Russia’s frozen assets.

In theory, redirecting Russian money into Ukraine ensures continuous resources and weakens Moscow. As Radosław Sikorski, Poland’s foreign minister, said “It’s very simple, either we use the aggressor’s money or we will have to use our own money.”

In any case, using frozen assets remains an economic lever rather than a military guarantee. It complements security by funding defense, but does not by itself deter invasion.

The evolving architecture of security guarantees for Ukraine reflects both strategic necessity and political realism. Since the 2023 G7 Joint Declaration of Support, more than two dozen nations have begun signing individualized defense agreements with Kyiv - covering long-term weapons deliveries, training, intelligence sharing, and industrial cooperation.

These bilateral pacts, such as Ukraine’s 10-year deal with the United States (June 2024), its comprehensive treaty with Germany (February 2024), and the “100-year partnership” with the UK (January 2025), operationalize deterrence by denial - strengthening Ukraine’s own capacity to repel invasion rather than promising automatic allied intervention.

Together, these instruments form a transitional security regime - one that deters renewed aggression without waiting for full NATO accession. Whether these guarantees can evolve into a lasting collective-defense system remains uncertain, but it has already redefined how the West conceptualizes security in the post-Cold War order.