Oleksandr Savchuk is a Ukrainian publisher, kobzar, scholar, lecturer, and co-founder of the literary residency Slovo. In 2010, he launched his own publishing house in Kharkiv, with a mission to revive forgotten names in Ukrainian science, culture, and art. Unique works in history, ethnography, philosophy, and art history—carefully edited before publication—are produced in a small print shop as aesthetically refined books.

Despite the full-scale Russian invasion and ongoing shelling of front-line Kharkiv, the publishing house continues its work actively. Moreover, in 2022, Oleksandr Savchuk opened a space called KnyhoUkryttia ("Book Shelter") to bring together like-minded people, which in 2024 evolved into a bookshop-café in the heart of Kharkiv.

In this interview, Oleksandr Savchuk talks with us about KnyhoUkryttia, running a publishing business during wartime, the cultural phenomena of his native Kharkiv, and the personal changes shaped by the war.

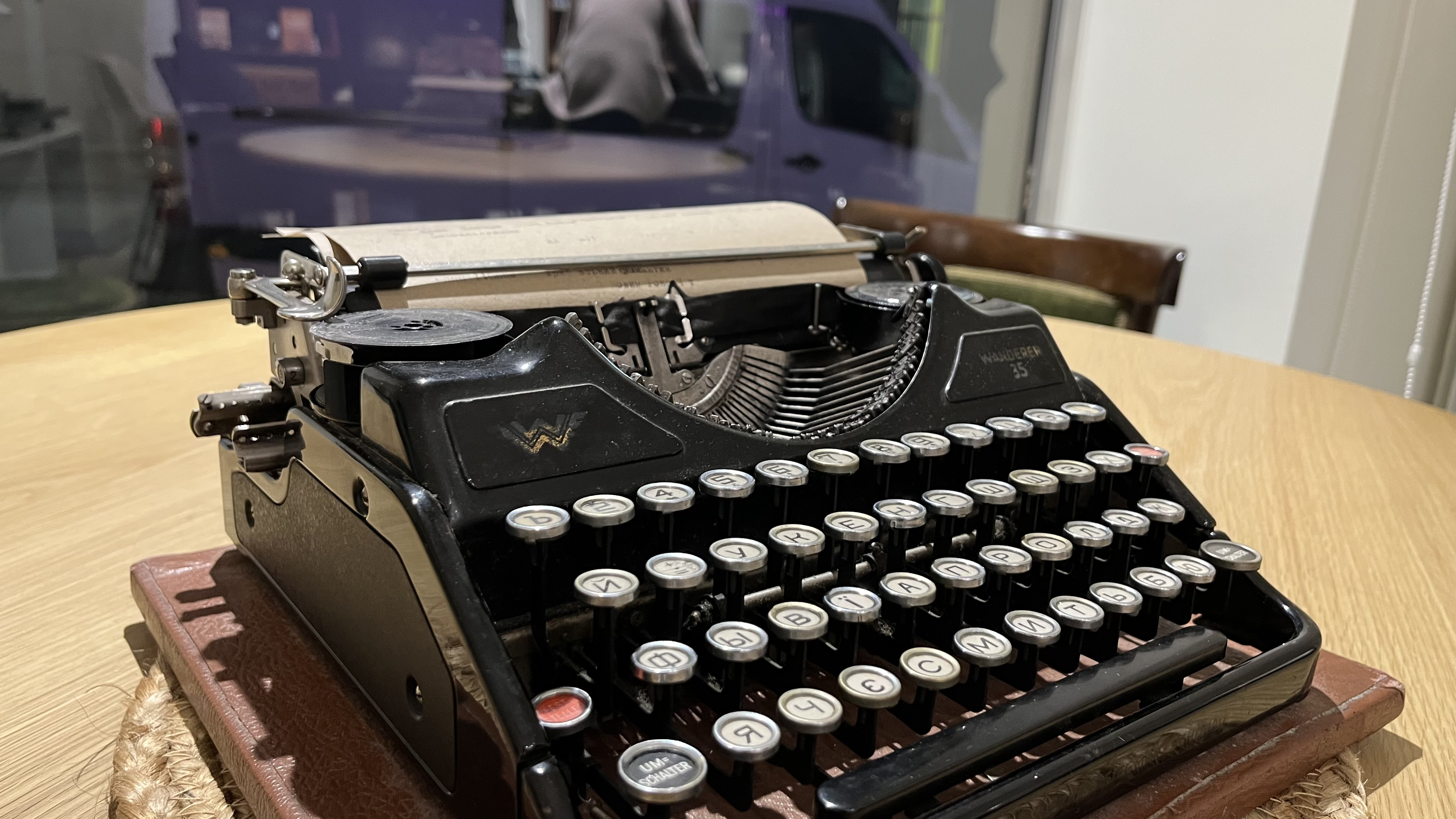

A bright and spacious place with a large book display, delicious coffee, and desserts, located at 14 Alchevskykh Street. Coffee tables with vintage typewriters, a small stage, and a projector for hosting events. It's a place where you can work quietly, attend a cultural or educational evening, or simply browse the shelves. Every book here is published by Oleksandr Savchuk's publishing house. Its values — in contrast to pragmatic business models — lie in depth rather than breadth.

After the full-scale invasion began, we resumed our work actively — and that's when the demand from Kharkiv residents appeared. We hadn't seen anything like it in the thirteen years before 2023. More and more readers started coming to our publishing warehouse. It became clear that the topics we explore in our books are still relevant. We have things to say.

As a lecturer, I thought it would make sense to organize semi-educational events and create a space where people could ask the questions that are troubling them right now. As it turned out, it was also a kind of psychotherapy. Just imagine: yesterday, people from Belgorod were visiting our restaurants — and today, rockets are flying from there to our city. For those who hadn't been interested in history or culture, this came as a shock.

Before the full-scale war, it was hard to imagine that we'd ever open a physical space. For the first year, we operated in a small semi-basement — that's where the name Knyhoukryttia comes from. We held events there and realized that we had formed a circle of people we could continue to invite. But there wasn't enough space, so in the summer of 2024, I decided it was time to take a risk — to rent a place in the city center and turn it into a café.

During my student years, there was nowhere I could go — I lacked this kind of cultural and educational context. Now, I have the opportunity to create that context. Back then, I never dreamed I'd hear the Ukrainian language spoken in the center of Kharkiv. But now I see young people speaking it naturally — and that brings me joy. When I connect my memories with the present, I see changes, and it's nice to know that our publications and the work of Knyhoukryttia have had an impact.

Here, we've created every opportunity to tell people about our books, because they're another tool that helps raise important topics — culture, or, say, art history. It's very hard to immediately explain who Narbut or Krychevskyi were, what wooden architecture is, or why only Bahalii managed to write a history of Sloboda Ukraine. That's why we organize events tied to these themes. And coffee and desserts — they're a pleasant bonus, creating a sense of comfort, coziness, and taste.

Obviously, the wartime conditions we've found ourselves in created a situation where we're not thinking about competition. There aren't that many of us, which has opened up more honesty and directness in communication.

During the war, it's been somewhat difficult to find staff — many people have left Kharkiv for other cities in Ukraine or gone abroad. But suppliers and contractors have stayed.

In some way, this circle of people has been filtered, and now there's more trust. Besides, given the constant threat of war, we all understand that we don't have the luxury of arguing — we understand each other better. Maybe that's just my personal experience, or maybe I've been lucky. I think we've worked together perfectly with the colleagues who helped me with Knygoukryttia. And there's also a circle of readers who always support us.

At the start of the full-scale invasion, I really wanted to stay in Kharkiv. I dreamed that the publishing house would resume its work, although I thought it was already the end. Then suddenly, one of our readers called to ask why we weren't sending out the books he had ordered. I told him we were under shelling and couldn't ship anything for now, but we had received his order.

In May, after Russian forces were pushed out of the Kharkiv outskirts and their field artillery could no longer reach the city, we resumed our publishing activities — the printing houses started working again. I called the customer back and asked whether he still wanted the books sent. After a long pause, he asked, with emotion: 'Are they intact?' — and when I said yes, he replied: 'Then send them!'

That's when I realized that our publishing house was still needed.

Books help — they save, support, redirect attention. And again, they tell stories of our recurring history, our attempts at independence, our relationship with Russia. That was the first time I felt the almost physical presence of culture — a bodily sense that reading gives you crutches. That is, a tool through which a person can lift themselves up and get going again. Since then, we've published about ten titles.

We want our books to look beautiful. We want print culture to be so strong it slows down the shift to e-books. In a way, this 'war' has already been won — half of all books are still printed, which is a great result considering the rapid digitalization happening around us. We've already launched several collaborations with other projects — from Kharkiv, Kyiv, and Lviv.

What happened to Faktor-Druk was painful for the entire publishing community. We print our books in our small bookstore, which has also come under fire. In the summer of 2022, we had a brush with death. I had just left the print shop, and less than a minute later, it was hit. The utility workers doing maintenance nearby were killed. I still remember them.

Most people in Kharkiv can tell you stories like this. During the first year of the full-scale war, the shelling was relentless — several times a day. We got so used to it that when the rockets stopped coming for a while, we started feeling anxious — something didn't feel right.

In a way, it's a test — whether what you're doing is 'just business.' But for me, publishing has never been just that.

At first, I didn't even plan for it to be a permanent operation. It was more like something that emerged out of necessity. For instance, take Porfyrii Martynovych's notes — they had to be published. It's incredible folklore that belongs on library shelves.

Every child should have free access to this kind of knowledge. Today, we truly appreciate every inquiry about topics like these, Because attention — attention is a huge challenge for the younger generation.

It's no secret that Kharkiv has a higher proportion of Russian-speaking residents. But we shouldn't worry too much about that. What matters more is: What kind of knowledge about Ukraine exists here in Kharkiv? How can we work with children — and with the people making decisions that affect the city?

Kharkiv has its own distinct cultural phenomena. Take the kobzar tradition, for example — it can't be overlooked. There are so many names, narratives, texts, and recordings tied to it. We need to speak about it boldly and with talent — without moralizing.

Another example: Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko, a Kharkiv native who essentially created the short-story genre.

There's room to debate how deeply the Executed Renaissance belongs to Kharkiv — after all, back then, many writers came here from other Ukrainian cities because it was the capital. But Kharkiv constructivism and the avant-garde? No debate there.

Yes, these movements were partially supranational. But they still reflect certain directions and capabilities Kharkiv has. For me, it has always been important to strike a balance between the ethnic, the traditional, and the modern — and Kharkiv does this in a fascinating way.

Ukrainian modernism in architecture is a hugely important story. It shows the drive, the ambition, the energy — the kind that could've been political, but instead manifested in art.

Kharkiv has the largest number of buildings from the era of Ukrainian modernism. This is a distinctly urban, Ukrainian, and elite architectural style — and it challenges the stereotype of Ukraine as solely rural or folkloric.

Architecture is something monumental, fixed in place — it holds a special position in our consciousness. I feel a particular fondness for it.

Right now, Ukraine is at a stage in its struggle for independence where these topics take on strategic importance.

With the start of the full-scale invasion, everything in my circle became much clearer. Maybe, for the first time, I stopped feeling like an outsider when walking into a store. These days, the Ukrainian language feels like a kind of protection, whereas the Moscow accent brings fear.

This war has brought enormous losses: people killed or gone, architecture destroyed, businesses closed, institutions vanished. I don't remember Kharkiv ever feeling this empty. We've descended into a kind of existential reduction.

There's less conflict, fewer ambitions — which means we're experiencing things more honestly, more fully. With daily threats all around, we don't postpone things. We say what we need to say to the people close to us — now. And that might be the most important thing we have left. It's just tragic that it came at such a cost.

But I don't know if people are even capable of such depth of feeling and reflection without a looming threat. We adapted so quickly, and now we try to find something positive in all of this.

And if that's even possible — well, then this is it.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It's content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.