The acclaimed TV series Chernobyl has shifted the usual cinematographic perspective on the topic. Portraying the disaster through personal stories at great length, it pieces together technical reasons, institutional flaws and the role of individuals. Its creator, Craig Mazin, largely based his story on the book Prayers of Chernobyl (also called Voices from Chernobyl) by Belarusian journalist Svetlana Alexievich. Although the Nobel Peace Prize winner, who signed the contract, was not given the credit, it was her interviews with Chernobyl liquidators and their relatives that brought real-life characters into Mazin’s drama. Yet, some of the witnesses of the nuclear accident see this adaptation as a major drawback in the HBO’s Chernobyl, among smaller historical details.

Serhiy Parashyn, a Deputy Director of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in 1986, argues that the mini-series distorts the behaviour of their management, and some ‘types of personalities do not match’. In particular, he refutes the brutal behaviour of the deputy chief engineer, Anatoly Dyatlov. Nonetheless, Parashyn admits Dyatlov was ‘directive’, but also ‘very smart’. ‘He did not stand any objections just because he knew everything,’ Parashyn assumes that was what betrayed his former colleague. He also believes Dyatlov’s toughness could have restrained the staff in their persistence to stop the slow reduction of power earlier and, in so doing, prevent the accident. However, Parashyn notes that neither the staff nor Dyatlov knew that the long expectancy for halting the power reduction would lead to an explosion.

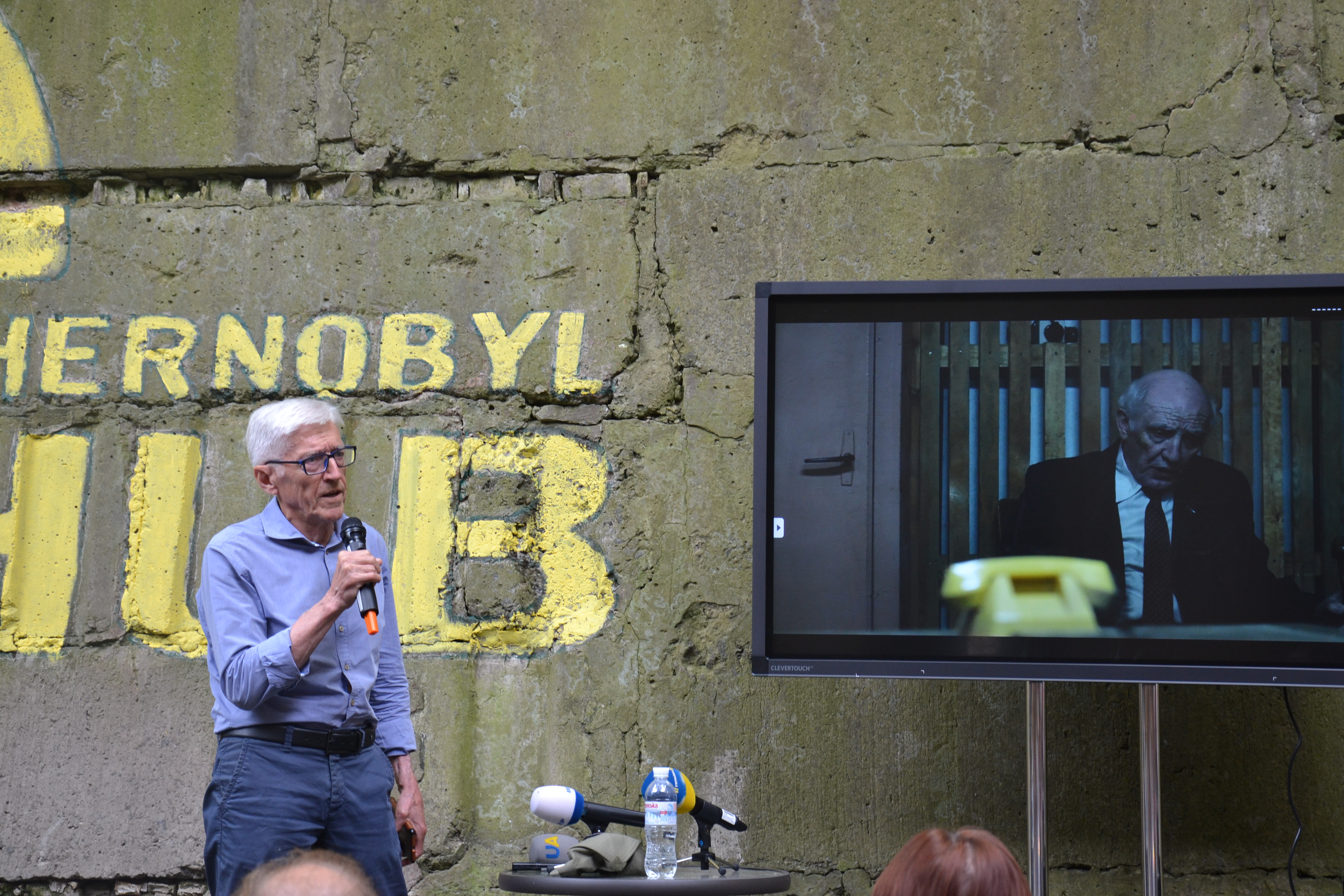

Recalling the director of ChNPP, Viktor Bryukhanov, Parashyn describes him as ‘a reserved, calm, intelligent man who duly carried through the whole situation’. An hour after the accident, he arrived at the power plant and met Bryukhanov in his office. The latter took the keys and they went downstairs for a meeting, which is depicted in the first episode of the mini-series. It was the same bunker where he now shares his flashbacks from that night: ‘What struck me was an immovable man carried out on a stretcher by two other men in white clothes. He died because of injuries sustained from the explosion,’ the former deputy director recalls his way to the bunker. Unlike today, he adds, ‘it was much darker here’. Unlike in the TV show, every head of the reactor shop had his own table. Here, they tried to understand what happened in each power unit in order to get a general picture of the situation.

Serhiy Parashyn commenting on HBO's Chernobyl

Serhiy Parashyn commenting on HBO's Chernobyl

In this sense, the atmosphere of chaos, disbelief and subconscious denial of the situation shown in HBO’s Chernobyl coincides with memories of the liquidators.‘The information was very contradictory for several hours. During the night, members of the operational staff were coming to report about the situation in different reactor shops but the radiation levels were so high that it was hard to believe,’ Parashyn says that in such a situation an outside perspective was needed to reduce the psychological pressure that was visible at the Chernobyl power plant during the accident.

‘After the accident, the psychological shock was so strong, that for several hours the leadership could not give proper orders,’ Parashyn recalls.

Under these circumstances, according to him, the chief engineer of the ChNPP Mykola Fomin ‘actually broke down’. His character is the most accurate of all those present in the TV drama.

Recognizing that the major responsibility for what happened lies with the senior management of ChNPP, the former deputy director says it was, primarily, a technical flaw in the construction of the reactor that led to the disaster. Hence, it is important to not discredit real persons through their TV characters. Oleksiy Breus, then operator of the 4th energy bloc confirms that, contrary to HBO’s depiction of the Chernobyl disaster, the hierarchy of authority had no place in the attitude of the management towards the operators. Instead, the atomists addressed each other in the same respective way (notably, not as ‘comrades’).‘Everyone was thinking about how to change the situation. It was tense, but nobody left,’ likewise other liquidators. Breus tells UkraineWorld that no-one questioned orders from the leadership, especially, in the aftermath of the accident.

Oleksiy Breus during the trip to Pripyat

Oleksiy Breus during the trip to Pripyat

In this vein, the scene with the so-called ‘divers’ does stick out of the general perception of duty in one’s job rather than the voluntary heroism of a Soviet man.

One of the three hailed liquidators, who went under the reactor to empty a water tank, Oleksiy Ananenko, assures UkraineWorld they simply obeyed orders. ‘I did not go there voluntarily. We could not have sent any man who had not known what to do. When I came to the station, they had already checked the dose there. I knew about it but I was not afraid.’ With simple respirators covering half of their faces, together with Boris Baranov and Valery Bespalov, Ananenko went three meters down to the corridors flooded with contaminated water. Unlike in the TV show, the level barely reached the knees because the firemen had already pumped it out. Likewise, their flashlights did not go off. Having followed the plan, he says they quickly found the wooden faucet, did their job and went back. Such bits of fictions from tHBO surely add more thrills to the depiction of the invisible danger on screen. However, the above-mentioned liquidators agree that the creators of the Chernobyl TV series could have been more sensitive in their extra-dramatization. Instead, they subtly doomed the ‘divers’ (two of whom are still alive) to a quick death.

While some parts of Chernobyl series are exaggerated, significant points are missing, Breus emphasizes.

For instance, the fact that the operators worked along with the firemen trying to normalize the work of the reactor. ‘It was important to show because it took the lives of many operators,’ the former Chernobyl operator stresses to UkraineWorld. Since his shift started in the morning, Breus received 20 annual doses of radiation in one day.

Since visualising radiation is the crux of the matter, Mazin and his team resorted to a number of tricks like radioactive particles in the air, or a dead bird hitting the ground. Instead, the consequences of irradiation or poisoning were not instantly evident, Breus recalls he noticed ‘a small spot’ under his eye ‘on the next or third day’. ‘However, we saw people who worked at night and in the morning, and they were all red,’ he adds. Amidst the living horror, Oleksiy Breus says there was no fear since the staff at the power plant simply took it as their job.

Oleksiy Ananenko, one of the three 'divers'

Oleksiy Ananenko, one of the three 'divers'

Out of all the main characters in the HBO TV series, Ulyana Khomyuk is the only fictional one. Nevertheless, the first suspicions of serious emissions of radiation, as well as fears over the possible second explosion, did indeed come from Belarus. In fact, Breus and Parashyn regard Khomyuk rather as a collective image of all scientists who sounded the alarm from abroad. In this context, the role of Valery Legasov, the scientist who is granted a decisive impact in HBO’s TV drama, is slightly ‘exaggerated’, Serhiy Parashyn states.

Despite this dramatization of characters and the details, HBO’s Chernobyl depicts well the Soviet obsession with the information vacuum.

Back then the head of the plant's Communist Party committee, Serhiy Parashyn, claims their primary task was ‘to prevent the panic’, which meant to not allow the truth about Chernobyl to be disseminated.

In the bunker with similar phones on the table, he now recalls that the outside connection was blocked, so they could only make calls to members of staff working at the power plant. ‘But we, those who grew up in the Soviet Union, perceived it as a natural process. After 10 years, when I went abroad, I was shocked to the same degree as during the accident. I saw what I had never imagined and read about things that ‘did not happen,’ Parashyn says, recalling the times when information started to be disclosed in the 1990s.

As a former party secretary, he also denies any pathetic reverence for the Party, such as the HBO’s scene with an elderly apparatchik giving a passionate speech about Lenin. ‘The Party did not interfere directly, which had its pros and cons,’ Parashyn says, recalling his own duty. ‘My task was to control the actions of the management staff to prevent an accident,’ which was the reason why Parashyn was dismissed in July.

Serhiy Myrniy at the checkpoint to Chernobyl exclusion zone

Serhiy Myrniy at the checkpoint to Chernobyl exclusion zone

Aside from many discrepancies, Chernobyl liquidators who experienced the accident and the aftermath themselves, rather indulge HBO’s successful attempt to draw attention to the topic again. Being critical of all cinematographic interpretations of the disaster, Serhiy Myrniy, commander of a radiation reconnaissance platoon in 1986, admits to UkraineWorld:

‘This film is definitely the most powerful and technically well-done expression on the topic of Chernobyl. Particularly so because it is made in the dominant cultural format.’

Now a director of science at the Chernobyl Tour, he hopes the TV series will have a long-term social impact in Ukraine and beyond. At least while Chernobyl is still a warning for other countries, Myrniy believes, the TV drama ‘is another step towards understanding the catastrophe and preventing new ones’.